R-Consonant as the hardest consonant sound

R-Consonant is one of the most challenging sounds in American English. This complex consonant sound has a great variety of pronunciations, complicated articulation and can be quite difficult for students of English to master. Due to its complexity and other factors, the R-sound is achieved the latest by typically developing English-speaking children. [2, p.1]

How can we help our students achieve a better, more natural American /r/?

The complexity of the sound causes so much confusion that it can be unclear how it works, how to learn and teach it. Naturally, there is a lot of subjectivity in intructions you can find for the American /r/.

Here, we attempt an evalution of some video instructions against relevant research data in the field to help better understand and find a way to master the American /r/.

Rachel's English Demonstration

English with Emma Demonstration

Speechy Things Lindsey's Demonstration

English with Gavin Demonstration

What can we conclude?

1. Articulation

We observed two tongue postures for the American /r/, the tip-up retroflex /r/ and the tip-down bunched /r/.

The tip-down bunched /r/ demonstrations.

The tip-up retroflex /r/ demonstrations.

Which way should learners of English use?

Some instructors prefer to teach the bunched /r/. For example, Rachel Smith supports her choice by claiming that curling the tip of the tongue upwards for the retroflex /r/ can result in dropping the jaw a little bit too much thus making the /r/ sound "hollow".

However, the majority of instuctors believe that it's easier to learn the retroflex /r/.

Is there any research to support either of these two preferences?

Actually, researchers observed a greater variety of tongue shapes and very different vocal tract configurations for this sound than just two shapes, the retroflex /r/ and bunched /r/ [3, 6, 9].

What are they?

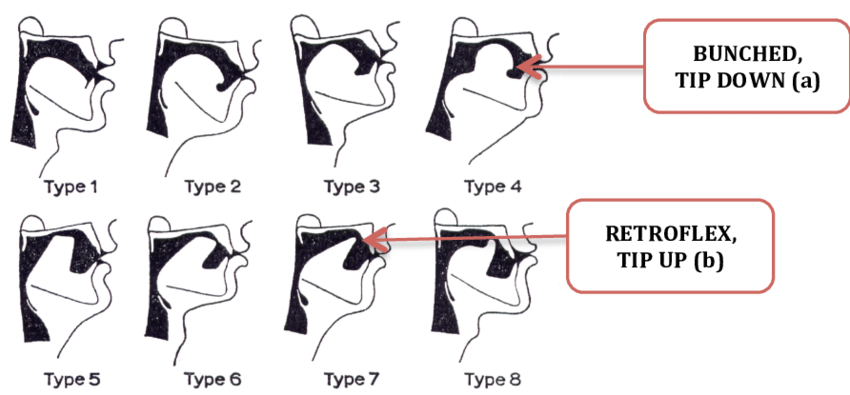

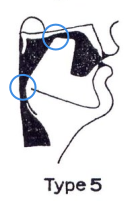

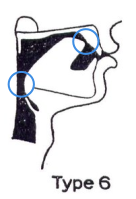

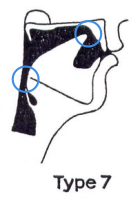

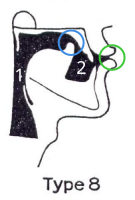

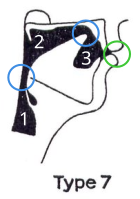

The Delattre and Freeman (1968) /r/ taxonomy has 8 types of tongue shape used to produce /ɹ/. [14]

Fig. 1 The Delattre and Freeman (1968) /r/ taxonomy

What can we observe in these diagrams? As consonant sounds are produced by means of constrictions in the vocal tract [15], we should pay attention to the places of such constriction. Constrictions are produced here by narrowing the vocal tract between the tongue and the pharyngeal wall, the tongue and the palate, and between the lips.

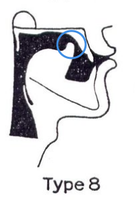

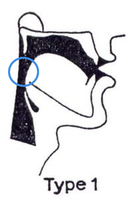

Types 1 and 8 are predominanetely observed in British English speakers and have only one tongue constriction.

Type 8 has only one tongue constriction, between the tip of the tongue and the palate. It's used for /r/ in the intial position (rat, relate) and /r/ in the middle position (arrest, coral, try). [14]

Type 1 is used for final /r/ in a word (far), or before a consonant (garb, berby). This sound is so soft, that the letter R is often believed to be mute here. Contrary to this belief, the /r/-sound is produced as the vocal tract still has one constriction (between the root of the tongue and the pharyngeal wall). [14]

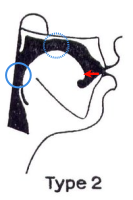

Fig. 2 British /r/ types with tongue constriction site circled

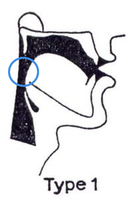

Whereas British /r/ has only two types, speakers of American English display a greater variety of tongue postures.

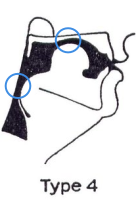

American /r/ is displayed in types 2 to 7. The unique sound of American /r/ is due to it having two tongue constrictions, one between the tip of the tongue and the palate, and another between the root of the tongue and the pharynx.[14]

Fig. 3 American /r/ types with tongue constriction sites circled

Combined with the lip constriction, the British /r/'s single tongue constriction form two resonance cavities, and the American /r/'s two tongue constrictions form three resonance cavities.

This three-cavity configuration is essential to articulatory characteristic of the American /r/. [14]

Fig. 4 British /r/ has two resonance cavities (on the left). American /r/ has three resonance cavities.

Type 2 is a weak American /r/ with wide palatal and pharyngeal constrictions. It differes from the British Type 1 as the tip of the tongue is withdrawn away from the front incisors, and the tongue is risen towards the hard and soft palates frontier.

Fig. 5 American /r/ Type 2 (on the left) compared with British /r/ Type 1.

Then, the sides of the tongue should be in contact with the sides of the palate and the upper molars for all types of /r/.

As it's been noted, this is a normal tongue position in English and other languages or, as it's called in research papers, postural basis for speech [4].

Even though this posture may be natural for some learners of English, it can be quite difficult for others to maintain it at all times. So it's worth keeping in mind, that maintaining the postural basis when speaking can help reduce the accented quality your voice has.

How exactly can it affect the sound of your voice? Apparently, a lower tongue posture than the postural basis changes resonance cavities' relative sizes, shifting resonance from one to another. Experimenting with the postural basis may give you some idea how it affects the way you sound.

Which tongue shapes serve for more natural American /r/ according to research data?

The American /r/ sounds best with the palatal constriction placed closer to the junction between the hard and soft palates [14, p. 42].

Whereas narrowing of the pharyngeal constriction helps to enhance the sound (described by the researchers as being subjectively rougher and harsher, having more "color"), widening it makes the /r/ sound mellowed. [14, p. 42]

If the goal is a louder "colored" /r/, narrower pharyngeal constriction and closer to soft palate palato-velar constriction (whether bunched or retroflex) would work best. Wider pharyngeal constrion combined with closer to alveols palato-velar constriction is bound to make /r/ sound softer.

Which of the two constriction sites is more important for the /r/ sound's quality?

As it was proved in ultrasound research, the pharyngial constriction is "essential for perceptually correct production of either vocalic or consonantal variants of /r/" [2, p. 552].

As to the tip-up/tip-down choice, we must encourage ESL students to explore as it was concluded in research of /r/ acqusition in children. In order to help children to acquire the /r/ sound, "it is important to encourage pharyngeal constriction while allowing to find the /r/ tongue shape that best fits individual vocal tract." [2, p. 552]

As narrow pharyngial constriction is responsible for most of the /r/ sound's quality, give a try to straining the throat muscles. It can help to tighten the pharyngial constriction and increase the sound effect of the American /r/.

Do these articulation differences matter? Is it nessassary to learn about different tongue postures?

Interestingly enough, researchers determined the listeners' accuracy in distingushing /r/ variations to be fairly poor. As it has been shown, the listeners are able to perceive the variant right in only 35-40% of the time. [7]

This is shown to be due to the adaptive nature of /r/ retaining its "auditory identity" even in very different pnonetic surroundings.[14, p.31]

Basically, it means that /r/ sounds more or less the same regardless of the sounds coming before or after it.To a great extent, this is achieved by a speaker using completely different tongue shapes in their speech, with up to 40% of American English speakers using both tip-down and tip-up [11, 13].

Naturally, the ability to use different shapes for the /r/ sound is acquired in childhood "during the exploratory period of acquisition". [16, p. 7] This conclusion should encourage ESL students to experiment more while learning pronounciation.

Are some types used more in some parts of the United States?

Type 2 is only used in Eastern New England ("Yankee dialect" in Maine, New Hampshire, and the eastern half of Massachusetts)

and the Coastal South (Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida). [14, p. 43]

Type 3 is the most used type of the American /r/ "from East to West". [14, p. 43]

Which tongue posture to master first?

A speech pathologist's tip:

A YouTube instructor's choice:

Different shapes of the vocal tract for /r/ can be used when it is "phonetically natural" to use one of them and not another.

An important note for students of English, often struggling with tension in articulators when learning new sounds. Employing various vocal tongue postures for /r/, more appropriate in different phonetic contexts, helps to lessen tongue displacement, muscle strain and stress [8].

Which tongue posture is appropriate in which phonetic context?

American English speakers tend to use the bunched /r/ next to "bunched" consonants and vowels /ʃ/, /k/ and /i/ (examples: shrine, shrink; creek, cruse; career, hear). [9, p. 711]

Retroflex /r/ is generally used next to:

- labials:

sounds requiring the participation of one or both lips, they are bilabial (two lips) consonants

/p, b, m/ (examples: prime, prom; brook, bread; shamrock, primrose)

and labiodental (one lip and the upper teeth) /f, v/, (examples: France, fry; vroom, chevron, fervor, reservoir)

- word boundaries: between words,

and, also, inside words: free stem words, stems that can stand free as words (examples: formation, mermaid),

whereas bound stems must occur in combination with at least one affix (examples: survive).

phonotactically constrainted words, where there must be a word boundary, since we never encounter the letter combination within a morpheme in English even if it's a single word (examples: forward, narwhall).

and back vowels /u, ʊ, o, ɔ, ɑ/ which are made with the back of the tongue raised (examples: rule, room, rook, brook, raw, rock) [9, p. 711; 12].

It's worth keeping it mind, that it is the constriction, not tongue shape, which accounts for "acoustic phenomena" of the American /r/. [14, p. 37]

Lips shape for the sound may vary depending on the position of the R-containing syllable. As shown in research, the lip rounding is generally present for this sound. [2, 3]

Types 1 and 2 always have some lip opening as they are only used afer vowel sounds (in postvocalic weak position) [14, p. 43].

How to check if you're doing it right?

Learners can use a mirror to see if the tongue shape is what they're trying to achive. However, it's more important to aim at acoustic or auditory target for each phoneme [11] since most tongue positions are normally very difficult to observe.

As we learned these important points from research, what can we conclude about the popular YouTube videos for the American /r/?

Rachel's English videos' instructions focus on the tip of the tongue position and lip position only and use the pictures showing wide space between the root of the tongue and the pharyngial wall. These pictures do not represent the American /r/ as they lack pharyngial constriction. Rachel Smith only mentions pulling the tongue "up into itself" with "the front part pulling back". In another video, the instructor discourages students from "pulling the tip of the tongue too far back" using the same misleading picture for the American /r/ lacking pharyngial constriction. As it is essential for the American /r/, the tip is misleading as misrepresenting the role of pharyngial constriction.

English with Emma's instruction focuses on auditory target providing very little in terms of articulation. However, the instructor mentions that the tongue should be pulled back for the bunched /r/.

Explaining the postural basis (the sides of the tongue position), the tip of the tongue and lip position, Keenyn Rhodes mentions only briefly the fact that the tongue should be pulled back for the /r/ when compared to such sounds as /l, n/. However, giving a summary of her tips, the instructor doesn't list pulling the tongue back making it look insignificant and unneccessary for the American /r/.

Conclusions:

1) maintain the postural basis for speech at all times;

2) keep the pharyngial constriction as narrow as it is comfortable, slightly strain the throat muscles for /r/;

3) experiment with the tongue shape (the palatal constriction);

4) aim at the auditory target.

2. R-Consonant Proper Sound

There are different opinions as how to teach the students the letter R's sound.

The two common ways to say R are /rah/ and /er/. Which one is correct?

Rachel Smith's R-Consonant demonstration begins as /er/.

Obviously, we do not say words like REST with /er/ but another sound for R as it is demonstrated in the video below.

On the other hand, we do not say R in REST as /rah/ either.

As Phonics instructors point out, the proper way to say the R-Consonant sound is neither /er/, nor /rah/. The confusion is caused by the fact that it's very difficult to say the R-sound in isolation. So we add a beginning or ending sound to it, getting it as /er/ or /rah/ respectively.Emma's R-consonant demonstration is closer to the true R-sound:

Emma's R-consonant demonstration in the word RED

is not unlike Rachel's in that they do not say ER-EST or ER-ED, but R-EST and R-ED respectively.

As Stephanie Headshot observes, the /er/ sound can be acceptable in teaching the R-sound to young children, who have difficulties producing the /rah/ sound.[1]

This audio is the children's Cambridge course (Super Minds 3, British English) /rah/ demonstration.

Thus, the first choice for students should be the /rah/ sound, provided they have no problem producing it with the proper instruction. Also, /rah/ would be the only correct choice for teaching consonant blends with r, (like br, dr, etc.). These blends should be pronounced as /brah/ and /drah/, not /ber/ and /der/.

3. Practice

Examples in difficulty level increasing order: deer, car, hair, corn, fire, tower.

The 32 common English words with strong and weak R.

Between Vowels R (Intervocalic): miracle, coral, arrest, erroneous (post-stress and prestress, with front and back vowels).

Preconsonantal: beard, assured, guard, garb, jargon (after front, center, or back vowels).

Post-consonantal: creek, cry, try, pry, crude (before front, center, or back vowels).

Interconsonantal: bird, berg, derby, dirk, girdle, curb. (In the pre-, post-, and interconsonantal positions, we varied the consonantal articulations among bilabial, apico-alveolar, and dorso-velar.)

Prevocalic (acquired last by children/learners [16, p.7; 2, p.7]): read, rat, rouge (Initial/r/ before a stressed vowel which is front, center, or back); robust, relate (/r/ before unstressed vowel which is back or front).

Final (strongest in /r/ in American English, weakest in British): poor, for, far, fair, fur, fear (/r/ follows a back, center or front vowel, or is the syllable peak), and offer (final /r/ follows an unstressed syllable peak or is the unstressed syllable peak).

Alveolar approximant (vector).svg - Lfdder

1. WHAT IS THE PROPER SOUND FOR R? January 7, 2016 by Brainspring link

2. A Multidimensional Investigation of Children's /r/ Productions: Perceptual, Ultrasound, and Acoustic Measures

June 2013 American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 22(3)

DOI:10.1044/1058-0360(2013/12-0137)

3. Adler-Bock M, Bernhardt BM, Gick B, Bacsfalvi P. The use of ultrasound in remediation of North American English /r/ in 2 adolescents. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2007 May;16(2):128-39. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2007/017). PMID: 17456891.

4. Liu, Y., Tong, F., De Boer, G., & Gick, B. (2022). Lateral tongue bracing as a universal postural basis for speech.

Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 1-16. doi:10.1017/S0025100321000335

link

5. Lieberman. The Evolution of Human Speech: Its Anatomical and Neural Bases.

Current anthropology. 48(1):39-66. doi:info:doi/

link

6. Zhou X, Espy-Wilson CY, Boyce S, Tiede M, Holland C, Choe A. A magnetic resonance imaging-based articulatory and acoustic study of "retroflex" and "bunched" American English /r/.

J Acoust Soc Am. 2008 Jun;123(6):4466-81. doi: 10.1121/1.2902168. PMID: 18537397; PMCID: PMC2680662.

link

7.

Twist, Alina & Baker, Adam & Mielke, Jeff & Archangeli, Diana. (2007). Are "Covert" /ɹ/ Allophones Really Indistinguishable?.

University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics. 13.

link

8. Ian Stavness, Bryan Gick, Donald Derrick, et al.

Biomechanical modeling of English /r/ variants.

The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 131, EL355 (2012); https://doi.org/10.1121/1.3695407

link

9. Mielke, J., Baker, A., and Archangeli, D. (2010). “Variability and homogeneity in American English /˙/ allophony and /s/ retraction,”

in Laboratory Phonology 10 (Phonology and Phonetics 4–4), edited by C. Fougeron, B. Ku¨hnert, M. d’ Imperio, and N. Valle´e (de Gruyter Mouton, Berlin), pp. 699–730.

link

10. Campbell F, Gick B, Wilson I, Vatikiotis-Bateson E. Spatial and temporal properties of gestures in North American English /r/. Lang Speech.

2010;53(Pt 1):49-69. doi: 10.1177/0023830909351209. PMID: 20415002; PMCID: PMC2894326.

link

11. Guenther, Frank H., Carol Y. Espy-Wilson, Suzanne E. Boyce, Melanie L. Matthies,

Majid Zandipour, and Joseph S. Perkell.

Articulatory tradeoffs reduce acoustic variability during American En-

glish /r/ production. 1999. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America

105:2854–2865.

link

12. ENGLISH PHONOLOGICAL ANALYSIS A Coursebook.

Published by the Department of English Linguistics Eötvös Loránd University. Budapest. 2013

link

link

13. Heyne, M., Wang, X., Derrick, D., Dorreen, K., & Watson, K. (2020). The articulation of /ɹ/ in New Zealand English.

Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 50(3), 366-388. doi:10.1017/S0025100318000324

link

14. DELATTRE, PIERRE and FREEMAN, DONALD C.. "A DIALECT STUDY OF AMERICAN R’S BY X-RAY MOTION PICTURE" ,

vol. 6, no. 44, 1968, pp. 29-68. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.1968.6.44.29

link

15. B.N. Pasley, A. Flinker, R.T. Knight, Speech Sounds, Editor(s): Arthur W. Toga, Brain Mapping, Academic Press, 2015, Pages 661-666, ISBN 9780123973160, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-397025-1.00062-2.

16. An ultrasound study of the acquisition of North American English /ɹ/ - Lyra V. Magloughlin - Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics, Vol. 19, 060071 (2013); https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4801030